KAMPALA – Uganda’s capital city, was eerily quiet on Saturday, Feb. 20, the day the Ugandan Electoral Commission announced the results of the presidential election held two days before. Even in Kabalagala, a lively district where people are usually partying at any time of day, the streets were empty. A few dozen young men sat huddled around a TV in a betting parlor, but they weren’t waiting for the election results; instead, a soccer game of the English Premier League flickered on the screen. “We know already who will win the elections and that is none other than Museveni,” one of them said. “We are more interested in how Arsenal is playing today,” he added, before turning his attention back to the screen.

Check also: Uganda police accused of stealing evidence in election controversy

The official results proclaimed a victory for incumbent President Yoweri Museveni, whose 61 percent of the vote was enough to avoid a second-round run-off, but not an overwhelming majority compared to what sitting presidents often garner in other African elections.

But in Kampala, nobody celebrated Museveni kaguta’s victory.

There were no cavalcades of cars, no spontaneous outbursts of joy in public squares. On the contrary, the military and police patrolled the streets, and civilians stayed at home. In the end, Museveni himself canceled the official celebrations.

That silence is not a symptom of routine acceptance of Museveni victories after 30 years of his rule, nor is it a recognition of the record of “steady progress” that the president had claimed for his administration throughout the campaign. Rather, it was the silence before the storm: While Museveni secured re-election, everybody in Uganda and the region realizes that this victory represents the beginning of the end of his grip on power.

The Old Man With the Hat

Seventy-one-year-old Museveni likes to play the benevolent grandfather of East Africa, a role that has earned him the sobriquet “the old man with the hat.” In 1986, he was the first of many African rebel leaders to successfully take power by force from an established government. Back then he claimed to represent a new generation of African ruler: democratic and with no relation to the corrupt and inept elites of the past. He pledged to rebuild the country, without the petty conflicts of self-interested political parties or the scourge of tribalism, while embedding his project in a vision of pan-Africanism. He served as a role model for many other victorious guerilla fighters-turned-rulers, some of whom remain in power as well.

Museveni’s long rule and prominence in continental politics make the February election, its aftermath and what comes next relevant far beyond Uganda’s borders. Ironically, Museveni—who once inspired movements to topple corrupt, geriatric and brutal dictatorships—has become a model for those very leaders themselves, yet another example of the continent’s authoritarian rulers who vie to extend their presidential terms.

But after 30 years in power, time is not on Museveni’s side. Uganda has the fastest growing population on the planet, 78 percent of which is below the age of 30 and has never lived under another head of state.

That generation of Ugandans sees their country’s politics as stagnating or even in decline. “Our country goes down the drain, but our president preaches something about ‘steady progress,’” one student complained at his graduation ceremony at Makerere University in Kampala. The public, particularly young people and the well-educated, believe that Museveni’s best times are behind him.

After 30 years in power, time is not on Museveni’s side.

They have a point. While in the 1990s Uganda was considered a success story in combating the HIV/AIDS epidemic, for example recent statistics are less flattering, particularly compared to other countries in the region. Neighboring Kenya and Tanzania, which also saw a steady decline of new infections and HIV prevalence in the 1990s, maintained low rates into the 2000s, while Uganda saw an uptick. Furthermore, economic growth has declined substantially over the past 10 years, falling to 4.1 percent in 2014 and just barely exceeding population growth. Museveni’s critics say it is time for fresh blood at the helm of the state.

But the president sees things differently. “I can’t leave while all we planted is just bearing fruit,” he said in one campaign speech. He still has unaccomplished visions, he argued, such as the creation of an East African Union. “I will go as soon as East Africa is united,” he said, implying that such a feat will occur under his leadership. In his speech he also promised to improve roads, schools and access to potable water and electricity. All he asks of Ugandans is to be god-fearing, generate wealth, and support the governing party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM), which for Museveni is the only entity capable of accomplishing those goals.

Despite opposition to his leadership, “the old man with the hat” has supporters, of course, especially in Uganda’s rural areas. The older generation still remembers Museveni as the freedom fighter he was in the 1980s, and women hold him in high esteem for having supported women’s rights. But there are clear signs that resistance is growing, especially among youth.

Cracking Down on Dissent

Uganda is Africa’s leading importer of tear gas. China delivered the latest batches just in time for election day, when the police used it liberally. After polling stations opened at 7 a.m. on Feb. 18, voting offices in many parts of Kampala hadn’t received their materials, and thousands of Ugandans waited for hours to vote. When, six hours later, trucks delivered ballot boxes without lids and already-opened packages of ballots, tensions escalated. Riots broke out, and some polling stations closed without a single vote being cast. Curiously, those irregularities largely impacted districts where the opposition was forecasted to do well a likely indicator of electoral fraud. Other districts, most of them dominated by Museveni loyalists, reported voter turnout rates close to or even reaching 100 percent. A statistical analysis of the voting records shows clear evidence of ballot-box stuffing in dozens of voting stations.

As the young men glued to the soccer match made clear, few Ugandans trust the electoral process. “The biggest worry is voter apathy that’s a high risk for the future of our country,” said Crispy Kaheru, director of the Citizen’s Coalition for Electoral Democracy in Uganda (CCEDU).

Still, politics is on everybody’s mind, and debates are furious, animating talk shows and social media, and stoking altercations in bars and on the street. But that popular frustration has combined with a certain resignation to being unable to change the status quo.

Museveni’s regime is aware of the danger of that mixture. When Ugandans woke up on election day, they turned on their cell phones only to find that they couldn’t access social networks such as Facebook, Whatsapp and Twitter. Internet access has penetrated even rural areas in Uganda and has become a game-changer for the government and opposition alike. According to the Ugandan Bureau of Statistics, 13 million Ugandans of a population of 36 million are online, most of them youths and young adults. Through social media, they had front-row seats when popular protests against longtime rulers escalated in Burkina Faso, where Blaise Compaore was driven from power in 2014, and Burundi last year.

Social media had already played a strong role in mobilizing Ugandans for post-election demonstrations in 2011, inspired by the protests that toppled leaders in North Africa and the Middle East. At the same time, Ugandans, well-aware of the chaos that followed those uprisings and the deadly crackdown that met similar dissent in Burundi, are wary of drastic change. “Nobody wants to go down that path,” said Kaheru. Still, “the risk of post-election violence is high.”

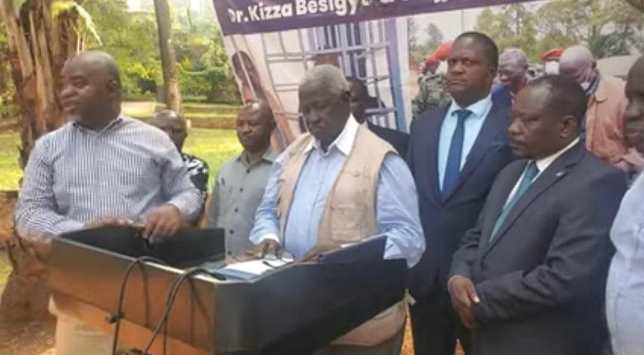

Ugandan security services came to the same conclusion. The day after the election, police, military police and soldiers from the Ugandan Special Forces Command (SFC) surrounded the headquarters of the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC). Young protesters were dispersed with tear gas, and rounds of live ammunition were fired into the air. Afterward, the police stormed the headquarters and arrested FDC presidential candidate and longtime opposition figure Kizza Besigye.

The SFC, which includes the Presidential Guard Brigade, is among the best-trained and equipped elite units in Africa. Trained by U.S. instructors, it is commanded by Museveni’s oldest son, Brig. Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who spent his quick rise through the ranks mostly at U.S. military academies. The SFC exemplifies Uganda’s ambitions to establish itself as a regional power. And it might be close to reaching that goal: Under Kainerugaba’s command, Ugandan soldiers are battling al-Shabab in Somalia and hunting the Lord’s Resistance Army in the Central African Republic. In South Sudan, they’re propping up President Salva Kiir against the rebels of former Vice President Riek Machar.

Since the elections, the SFC has become a common sight in the streets of Kampala as well, searching cars for weapons and looking out for troublemakers. Its domestic presence reflects the regime’s increasing instability and complete reliance on the security forces to maintain control.

Since national security forces stormed the FDC headquarters in February, Besigye has been under de facto house arrest, with his villa surrounded by a battalion of police and military. Spike strips secure the driveway, while journalists are dispelled with pepper spray. Even his lawyers and party officials are not allowed to visit. When he has tried to leave the compound, he has been snatched by police and driven off, only to be subsequently released.

Uganda is Africa’s leading importer of tear gas. China delivered the latest batches just in time for election day, when the police used it liberally.

The Ugandan police have arrested Besigye in this fashion at least a dozen times since the elections, each time without a criminal charge, though police chief Kale Kayihura has accused him of planning violence and mass protest. The arrests are nothing new for Besigye: He led the 2011 protests, which the regime is determined to prevent from reoccurring.

After gaining access to Besiyge’s home, European Union, U.S. and United Nations representatives strongly criticized what they called his unlawful detention. In a statement following a call between Secretary of State John Kerry and Museveni, the U.S. State Department called for Besiyge’s release from de facto house arrest, arguing that “Uganda’s progress depends on adherence to democratic principles in the ongoing election process.” That rhetoric marks a shift in tone, at least, in U.S. policy, which has significantly supported Uganda’s security forces, including its special forces.

Meanwhile, Besigye’s supporters and sympathizers face similar repression, but remain defiant. In April 2015, central Kampala was put on lockdown for hours when a horde of pigs dyed yellow, to reflect the NRM’s party color was set loose in front of the president’s residence.

Besigye served as Museveni’s personal doctor and held the rank of colonel during the civil war in the 1980s. He isn’t the only ex-military-turned-opposition figure to be arrested in the wake of the elections, either. Gen. David Sejusa, who was the former national intelligence coordinator and a senior adviser to Museveni, was also detained by security forces. Sejusa had already fled to the United Kingdom in 2013 after publicly expressing the need to “build alternative capacities” to Museveni’s rule. “No one should imagine that Museveni will be removed through elections,” he said in his controversial statement. He since returned to Uganda, perhaps prematurely, as his arrest suggests.

A Family Affair

Sejusa’s criticism of Museveni largely revolves around the president’s apparent attempts to appoint his son, Muhoozi, as his successor. Older army generals have rejected that move, disapprovingly eying the 41-year-old’s fast rise through the ranks: Muhoozi commands the special forces, making him one of the most powerful officers in the military, if not the most powerful. Museveni has traditionally enjoyed strong support from the security services, and can count on them to insulate his power from protests on the street. But that reliance could backfire if his succession plans don’t earn the military elite’s approval—a near certainty if he tries to keep the power within his family, the members of which already hold numerous official or unofficial posts in government.

Museveni’s home on the shores of Lake Victoria 25 miles from Kampala, originally a colonial-era villa, is evidence of his corrupt leadership and personal wealth. In preparation for the 2007 Commonwealth Summit and reception of Queen Elizabeth II, Museveni had it lavishly extended; its facade and size are now reminiscent of the White House. The offices lining the long corridors are filled by over 100 presidential advisers, many of whom are Museveni’s family members. The government’s roster reads like a family tree. The president’s sister is the administrator; her husband is responsible for the presidency’s finances and accounts; Museveni’s daughter is his private secretary; and dozens of nephews and nieces, cousins and in-laws constantly come and go. The Special Forces Command is headquartered next to Museveni’s compound. Not surprisingly, its commander Museveni’s son, Muhoozi is married to the daughter of Uganda’s foreign affairs minister, bringing the foreign policy portfolio into the family as well.

“[Museveni] has personalized all institutions of the state, putting in place an immense system of patronage that is tailored exclusively to him,” said Patrick Mwambutsya-Ndebesa, Uganda’s leading historian who has studied Museveni’s power politics and relationships intensively.

The problem is that Museveni can’t run for president again in 2021; beyond term limits, the constitution bars candidates above 75 years old. Succession has therefore become the key question that must be resolved within the next five years.

Loosening Museveni’s Grip

So who are the alternatives? Apart from Museveni’s obvious family favorites, one promising contender is John Patrick Amama Mbabazi, commonly called JPAM—until recently considered to be Uganda’s second-most influential politician. JPAM, also of the NRM, was prime minister until 2014, and, as a regime insider, knows all of its secrets and tricks. His past posts include the head of Uganda’s foreign intelligence agency, minister of justice, minister of defense and minister of security, as well as secretary-general of the NRM. He has long been considered a likely successor to Museveni.

“Our families were very close—for 42 years,” his wife, Jacqueline Mbabazi, recalled in an interview, pointing to the garden where Museveni’s son once played with her own children. Now, however, the two families are bitter enemies. As she told it, Museveni and her husband had a kind of gentleman’s agreement that Museveni betrayed by running in 2016. “Museveni became so greedy and always talked of ‘his oil,’ ‘his money,’ as if the whole country would belong to him,” she said angrily.

The government’s roster reads like a family tree.

At her prodding, Mbabazi split from the NRM and ran in the February election. Although his candidacy floundered—official results indicated that he received only 1.5 percent of the vote—it symbolized the deep divisions that wrack the ruling NRM. Insiders like Mbabazi and Sejusa are beginning to think about positioning themselves for when Museveni is no longer around.

Mbabazi challenged the election results in court, and his case will be heard before the end of March. But Uganda’s judiciary isn’t exactly independent, and the results likely won’t be annulled as a result of his petition. Still, the proceedings will put additional pressure on Museveni, which may prompt more party defections in the future.

Museveni and his entourage seem well aware of that risk and are trying hard to come up with a strategy to fight the emergence of a viable political opposition. One government initiative, the Crime Preventers, has some worrying historical precedents: The group is essentially a police-organized youth militia that, according to a superintendent, “helps [the police] find suspects in their communities who plan a crime.” Members, who sport white t-shirts emblazoned with their official title, are already active in villages and towns all over the country. When asked about the program’s size and membership, Kayihura, the police chief, evaded the question, stating only that his “goal is to have the whole Ugandan population signed up as crime preventers. Their task is to prevent crimes. That has nothing to do with the elections.”

Still, the initiative emerged suspiciously close to the elections, at a time when observers increasingly saw the combination of Besigye and Mbabazi as a formidable challenge to Museveni.

Although the Crime Preventers can be seen marching and singing under police supervision, their organizational structure, training, orders and financing are treated as state secrets. Their shadowy nature and political ties earn them obvious parallels to the region’s other youth militias, such as Burundi’s Imbonerakure or Rwanda’s Interahamwe, which the governments of those countries have deployed to violently suppress political opponents and protest movements.

Already, Ugandans are afraid to express their opinions in communities where the Crime Preventers are present, according to Kaheru, of the CCEDU. Some opposition parties have reacted by forming their own youth militias, creating a dangerous, cyclical dynamic. Museveni and Kayihura, his loyal supporter, see the Crime Preventers as insurance against any attempt to turn the police apparatus against them another element of the presidential patronage network that can be utilized at will against political dissidents should the need arise.

Student supporters of opposition leader Kizza Besigye burn posters of Museveni,

Kampala, Uganda, Feb. 15, 2016

Of course, patronage doesn’t come cheap. The Alliance for Election Campaign Monitoring a loose coalition of civil society activists advocating for increased transparency in party and campaign financing in Uganda, supported by Transparency International calculated that the election was the most expensive in Uganda’s history, with the NRM having spent about $37 million by November, before the campaign even started. The FDC, in contrast, only spent $380,000 in the same period. And the NRM’s money hardly came from its supporters: According to the European Union’s final electoral observation report, the party routinely misappropriated government funds for its campaign. Other reports mention “bags of money” that were handed out to local NRM elites at the party’s headquarters to shore up loyalties.

Those tactics have terrible consequences for state finances. In January, the Uganda Revenue Authority authorized a list of 150 companies, among them some of the country’s top taxpayers, which wouldn’t be required to pay taxes from January to June 2016. Insiders reported that the move was compensation for corporate campaign contributions to the NRM. As a result, Museveni will begin his new term with the government coffers empty, further undermining his ability to fulfill his campaign promises of building new roads, electricity infrastructure and hospitals, and creating jobs. Popular frustration, particularly among unemployed youth, will only rise, and the economy will suffer.

Uganda’s economic and political instability doesn’t bode well for the region at large. The country is one of East Africa’s economic motors, and Museveni has a diplomatic hand in every conflict in the region, from Somalia to South Sudan to Burundi, where he is the official mediator. By monopolizing power, deepening patronage networks and entrenching corruption and authoritarianism, Museveni is not only destabilizing his own country, but potentially East Africa at large. That makes the failure to responsibly manage his succession and provide economic opportunities to Uganda’s surging population a nightmare for Uganda, but also for the region.

Source: worldpoliticsreview

Check also; Diaspora: what Ugandans in diaspora think about Museveni’s 30 years in power

Bobi wine sent a message to the government about cancer machine

For the latest on national news, sports, politics, entertainment and more like our facebook page and follow us on Twitter.

This is not a Paywall, but Newslex Point's journalism consumes a lot of time, hard-work and money. That's why we're kindly requesting you to support us in anyway they can, for as little as $1 or more, you can support us .Please use the button below to contribute to Newslex Point, Inc. using a credit card or via PayPal.

Newslex Point News in Uganda, Uganda news

Newslex Point News in Uganda, Uganda news